The Tuskegee Airmen were the first black military aviators in the U.S. Army Air Corps, the precursor to the Air Force. Trained at the Tuskegee Army Airfield in Alabama, they flew later in Europe and North Africa during World War II.

At the time, racial segregation was mandated in the U.S. Armed Forces and across the country. Then on December 27, 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced an experimental civilian pilot training program. When the program began in 1939, there were 330 openings, none of which were located at black colleges.

After the Civilian Pilot Training (CPT) Program became permanent, and with pressure mounting from a lawsuit by Howard University student and civilian Pilot Yancey Williams, black newspapers, and organizations like the NAACP to include black civilians, with support from President Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, a flight school was founded at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Now known as the Tuskegee University, the first class had 13 students, with five successfully completing their training. These and later graduates became known as Tuskegee Airmen.

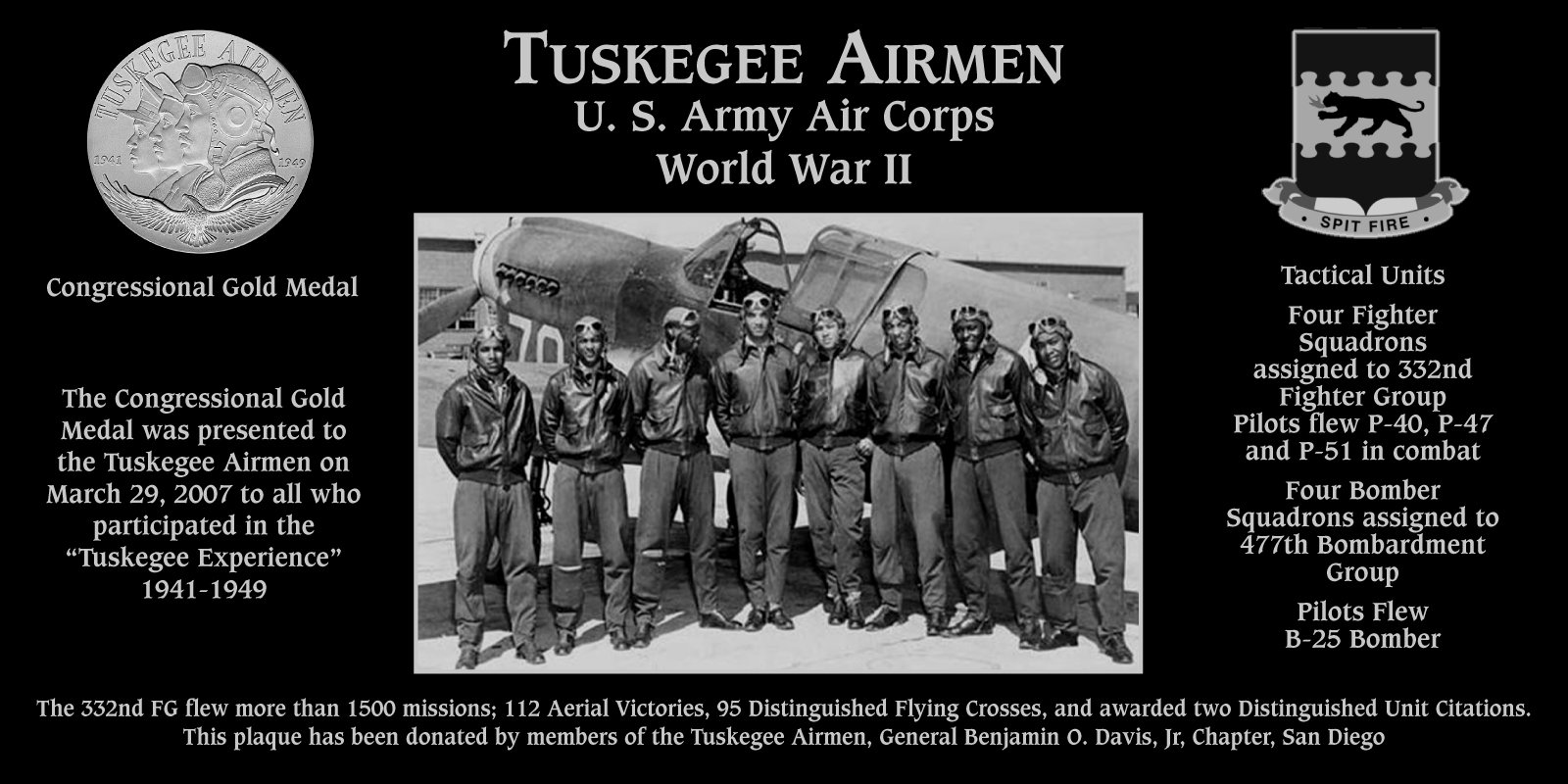

Among the inaugural 13 members of the first class of aviation cadets in 1941 was Benjamin O. Davis Jr., a graduate of West Point and the first African American General of the Air Force. The other four who successfully completed the program were commissioned second lieutenants, and all five received their Army Air Corps Silver Pilot Wings.

In addition to some 1,000 pilots, the Tuskegee program trained nearly 14,000 navigators, bombardiers, instructors, aircraft and engine mechanics, control tower operators, and other maintenance and support staff. Many of those trained pilots went on to serve in the 99th Pursuit Squadron (later the 99th Fighter Squadron) and the 332nd Fighter Group.

During the war the airmen served in both North Africa and the Mediterranean theater. 66 Tuskegee pilots were killed in combat, and 32 pilots were shot down and/or became prisoners of war. They were called “Black Birdmen” by the Germans and earned the nickname “Black Redtail Angels” by Americans for their vivid red marks on their aircraft.

The heroic actions of the Tuskegee Airmen resulted in shooting down 409 German aircraft, destroying 950 ground units, and the sinking an enemy destroyer utilizing only machineguns and expert flying tactics.

Their most distinguished achievement was protecting friendly bombers during 2,000 escort missions and never losing a single friendly bomber. To date, no other fighter unit has flown these many missions without a single loss.

This earned them two Presidential Unit Citations for outstanding tactical air support and aerial combat. After their brave service, the Tuskegee Airmen returned home where they continued to face racism and segregation due to Jim Crow laws. Despite this, their sacrifices allowed the nation to take a step forward and begin racial integration of the military. In 1948, President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981, which desegregated the U.S. Armed Forces and mandated the equality of opportunity and treatment for everyone, regardless of race.

After their brave service, the Tuskegee Airmen returned home where they continued to face racism and prejudice. Despite this, their sacrifices allowed the nation to take a step forward and begin racial integration of the military. In 1948, President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981, which desegregated the U.S. Armed Forces and mandated the equality of opportunity and treatment for everyone, regardless of race.

Charles S. Abell, Former Assistant Secretary of Defense said, “the character, courage, and commitment of the Tuskegee Airmen paved the way for their military comrades of every hue and color, race and creed to serve their Nation in combat side by side. Their selfless sacrifices have taught each new generation of Americans the true meaning of the American Sprit—Unity, Resolve and Freedom.”

Many Tuskegee Airmen went on to participate in other causes to further the rights of African Americans across the nation. Some chose to stay in the military, like Benjamin O. Davis Jr., who became the first black general in the new U.S. Air Force; George S. Roberts, who became the first black commander of a racially integrated Air Force unit before retiring as a colonel; and Daniel James Jr., who became the nation’s first black four-star general in 1975.

The Tuskegee Airmen were awarded 8 Purple Hearts, 14 Bronze Stars, 3 Distinguished Unit Citations, and 96 Distinguished Flying Crosses for their service during WWII. Their service transcended the war and led the way for future generations of service members.