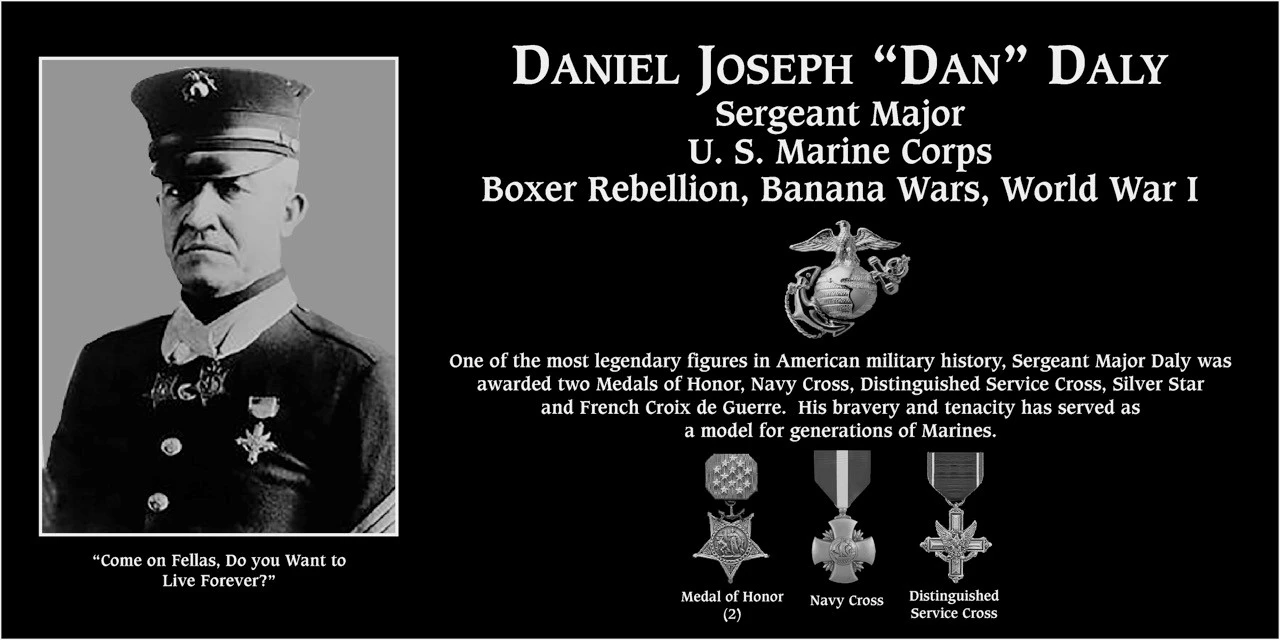

Daniel Joseph Daly

| Era | WWI |

|---|---|

| Branch | U.S. Marine Corps |

| Rank | Sergeant Major |

| Military Decorations | Distinguished Service Cross Medal of Honor Navy Cross |

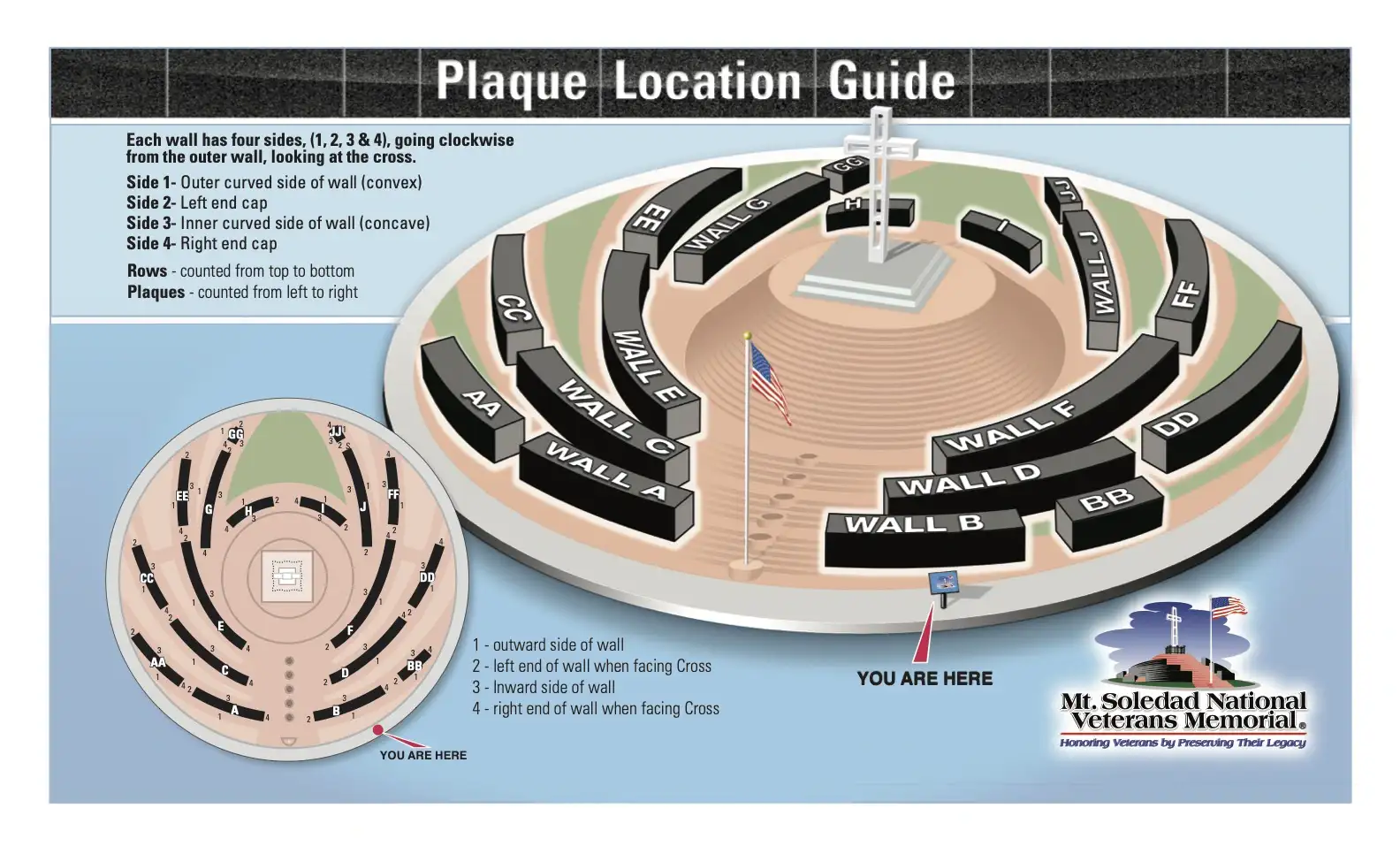

| Wall | BB |

| Wall Side | 2 |

| Row | 4 |

| Plaque Number | 1 |

One of the most legendary figures in American military history, Sergeant Major Daly was awarded two Medals of Honor, Navy Cross, Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star and French Croix de Guerre. His bravery and tenacity has served as a model for generations of Marines.

Medal of Honor (2), Navy Cross, Distinguished Service Cross

American Heroes: Sgt. Mjr. Dan Daly, USMC

We all know the military’s highest honor for valor is the Medal of Honor (MOH), but did you know how incredibly rare it is for anyone to receive it more than once? To date, the MOH has been awarded to 3,492 people; of those, just 19 have been awarded the MOH twice; 14 received 2 separate MOHs for separate actions, and one man comes to mind for having been up for a third MOH. But when he was brought up for that third MOH, the powers-that-be backpedaled, not sure about awarding one man three MOHs, so they opted to award him something else in its place. So who is this man who is such a fierce – yet selfless – fighter that he’d be up for a third MOH? He’s a Marine, of course, by the name of Sergeant Major Daniel Joseph “Dan” Daly. And this is his story.

Daly was born in Glen Cove, New York, on November 11, 1873. There is surprisingly little known of his childhood or his early years in general, but it is known he worked the streets of New York as a newsboy for some time. What’s also known is Daly made something of an early career as a boxer despite his being just 5’6” and tipping the scales at 132 pounds. Right from the start, Daly was a fighter, and as time passed it would become clear just how tenacious he was.

Tales of the Spanish-American War and Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders apparently spurred Daly to enlist, and so he did, on January 10, 1899. He enlisted in the United States Marine Corps and set about making his mark on boot camp, which was a different creature more than a century ago than it is today. Of course, the Spanish-American War was long since over by the time he got out of boot camp, so he was assigned to the Asiatic Fleet. If Daly was at all disappointed by not immediately rushing into combat, he didn’t have to wait long, because the Boxer Rebellion was right around the corner.

Japanese troops during the Boxer Rebellion.

The Boxer Rebellion came about as the result of a secret Chinese organization known as the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists, who led an uprising based on the idea that Western and Japanese influence had to be stopped. That “secret” society had been attacking and murdering foreigners and Chinese Christians for years prior to the uprising, and it came to a violent head when it spread to Beijing, where they killed Christian missionaries and Chinese Christians, also destroying churches and other buildings. On June 20, 1900, a siege on the foreign legation district – which was where foreign diplomats resided – began, and the next day Qing Empress Dowager Tzu’u Hzi declared war on each and every foreign nation with diplomatic ties in China.

That’s a quick summary, but what’s really interesting is where the Boxers got their name. The rebels came from all walks of life but were heavily populated by peasants who blamed their poor lifestyles on foreigners, and in order to become proper fighters they did a series of ritual movements and martial arts. To many those ritual movements looked like shadow boxing, which led to, you got it, “Boxers” and the name stuck. Now, what’s so interesting about those ritual movements? The Boxers believed their careful practices made them invulnerable to modern weaponry, including bullets. And they were about to put those beliefs to practice, because the Marines were coming, and with them, Dan Daly.

Daly and the other Marines were deployed aboard the USS Newark, which was bound for Taku Bay, China. After their arrival they were to head for Peking; other Marines had been stationed on Tartar Wall, which was just south of the American legation, but they’d been driven away by enemy fire. Then-Private Daly, led by Capt. Newt Hall, mounted the wall along with his fellow Marines, hell-bent-for-leather on taking the position back. Remember, this was 1900, and the Marines were armed with bayoneted rifles; combat was an intense, face-to-face bloodletting. The men took the position back, and on August 14, Capt. Hall and the others left to gather reinforcements and supplies to rebuild fortifications. Private Dan Daly was left standing guard entirely on his own.

It didn’t take long for the enemy to strike. Surely they saw the lone man standing guard and believed he could easily be defeated, but he wasn’t just any man, he was a Marine – and he was Dan Daly. The Boxers attacked armed with rifles, torches, swords – whatever weapons they could get their hands on – and Daly knew he had to stand his ground. The fight was on, and Dan Daly was about to prove he was just the Marine for the job.

Some accounts say Daly was armed with just a bolt-action rifle and bayonet while others say he had a single machine gun, and it is possible he had the latter. The M1895 Colt-Browning machine gun, chambered in 6mm Lee Navy, was issued to some Marines during the Boxer Rebellion, so it is possible Daly had one. Regardless of whether he had a rifle or one of the old potato diggers, as the M1895 was called, he was about to make an incredibly brave stand.

Throughout the night Daly repelled repeated attacks by the Boxers. They wanted to destroy the consulate – and anyone within it – and it was up to Daly to stop them. And he did. Marine Corps legend has it that when reinforcements arrived in the morning the bodies of 200 dead Boxers littered the ground around the wall where Daly had held the position, all on his own, all night. Although some historians say the number must be exaggerated, those who know the lion-like heart and courage of Marines in combat know it is most likely accurate. Dan Daly was awarded his first Medal of Honor for his actions that night, the official citation for which is sadly lacking:

“The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor (First Award) to Private Daniel Joseph Daly (MCSN: 73086), United States Marine Corps, for extraordinary heroism while serving with the Captain Newt Hall’s Marine Detachment, 1st Regiment (Marines), in action in the presence of the enemy during the battle of Peking, China, 14 August 1900, Daly distinguished himself by meritorious conduct.” (Pvt. Dan Daly’s first MOH citation, awarded July 19, 1901)

The years between his first and second MOH were riddled with acts of bravery, all of which would take far too long to list here, so we’re jumping ahead to 1915. The U.S. Occupation of Haiti began officially on July 28, 1915, although the first forces to touch down had actually arrived on January 27, 1914. In the years leading up to U.S. involvement, from 1911 to 1915, a number of forced exiles and assassinations meant the president of Haiti changed a whopping six times. When President Woodrow Wilson ordered 330 Marines to Port-au-Prince, Haiti, in 1915, it was with the specific order from the Secretary of the Navy to “protect American and foreign interests.” And so, Daly was sent to Haiti, where his heroism would save the lives of his fellow Marines.

At this point Daly was a Gunnery Sergeant, and his 35-man platoon had been sent on a reconnaissance mission in the Haitian countryside. On October 24, 1915, the Marines were crossing a river when they were ambushed. There were an estimated 400 Haitian Cacos rebels firing at the platoon from all sides, and although the Marines managed to battle their way across the river and set up a defensive position, things were grim. Their machine gun had been lost in the river during the initial attack, they were badly outnumbered, and night was falling. But they hadn’t counted on Dan Daly.

During the middle of the night, Daly snuck away from the relative safety of the Marines’ defensive position and returned to the river. Slipping beneath the inky surface of the river where his fellow Marines had spilled their own blood just hours earlier, he began his search for the dropped machine gun. By some miracle, he found it, strapped it to his back, and returned to his platoon. All without being detected. When morning broke the Marines were able to form a much better defense and began sweeping through the jungle, pouring machine gun fire into the rebels. When the dust settled and the brass stopped flying the Cacos rebels were thoroughly trounced, and Daly was awarded his second Medal of Honor. But he wasn’t done yet.

Daly being awarded the Médaille militaire.

Next came World War I, and Dan Daly, now 44 years old, wasn’t going to miss a chance for a good fight. Daly had a number of amazing moments during World War I, including three that resulted in his being awarded more combat medals. Those actions including his going to the rescue of 6 wounded Marines who were pinned down by heavy enemy fire, his capturing 13 German soldiers entirely on his own, and the shockingly courageous moment when he captured a machine gun nest by himself armed with just his Colt .45 and a few hand grenades. He also extinguished a fire in the ammunition dump at Lucy le Bocage. All these actions took place over just a few short days in June of 1918, and it was those actions that resulted in his being brought up for a third Medal of Honor. Unfortunately, as mentioned at the start of this story, the brass hesitated to award three MOHs to one Marine, so they instead awarded him the Distinguished Service Cross and Navy Cross for his actions at Belleau Wood.

“The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to First Sergeant Daniel Joseph Daly (MCSN: 73086), United States Marine Corps, for repeated deeds of heroism and great service while serving with the Seventy-Third Company, Sixth Regiment (Marines), 2d Division, A.E.F., on 5 June and 7, 1918 at Lucy-le-Bocage, and on 10 June 1918 in the attack on Bouresches, France. On June 5th, at the risk of his life, First Sergeant Daly extinguished a fire in an ammunition dump at Lucy-le-Bocage. On 7 June 1918, while his position was under violent bombardment, he visited all the gun crews of his company, then posted over a wide portion of the front, to cheer his men. On 10 June 1918, he attacked an enemy machine-gun emplacement unassisted and captured it by use of hand grenades and his automatic pistol. On the same day, during the German attack on Bouresches, he brought in wounded under fire.” (Official citation for Dan Daly’s Distinguished Service Cross.)

USS Daly

We’re all familiar with Belleau Wood, and many are also familiar with the famous words credited to Dan Daly during that battle. Daly was a First Sergeant during Belleau Wood, and at one point during the battle, his men were pinned down and outnumbered by two-to-one. The Marines had been battling the Germans for hours, and many were beginning to lose hope. Seeing this, and knowing from long experience the best action was, well, action, Daly rose up among his men and bellowed, “For Christ’s sake, men, come on! Do you want to live forever?” And then, in true Daly style, he led a successful charge. In Marine Corps lore Daly is said to have yelled “Come on you sons of bitches, do you want to live forever?” But it was Daly himself who told a historian the words he uttered, so we’re giving the account of the man himself.

Daly passed away on April 27, 1937. His memory lived on in the form of the American destroyer DD-519, the USS Daly. The Daly saw 27 months of service during World War II, fighting in the Pacific Fleet and earning 8 battle stars. The Daly also received one more battle star for Korean War involvement. She was commissioned on March 10, 1943, and decommissioned May 2, 1960.

Dan Daly was a badass Marine whose loyalty and single-minded determination to stand his ground and protect his fellow Marines makes him an American Hero like no other. He was a Marine who got the job done, no matter the risk to himself; he was the epitome of everything a Marine should be. Semper Fi, Sergeant Major.

Plaque Wall Map