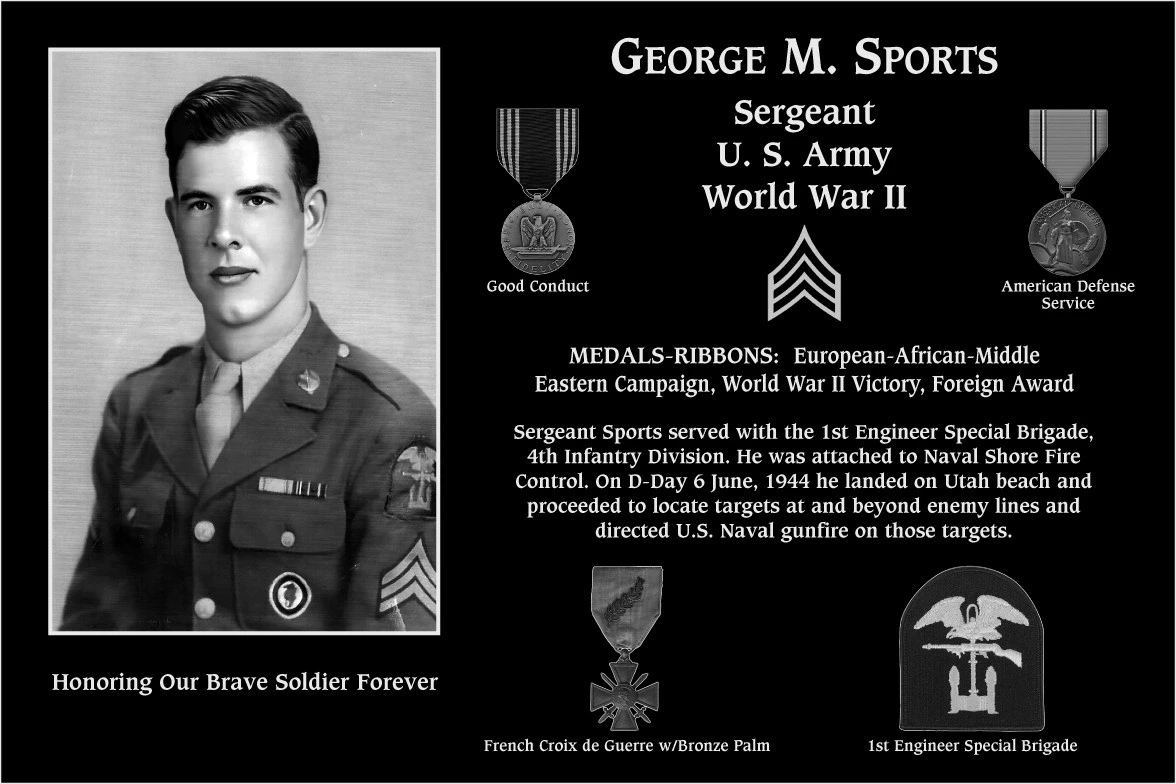

George M. Sports

| Era | WWII |

|---|---|

| Branch | U.S. Army |

| Rank | Sergeant |

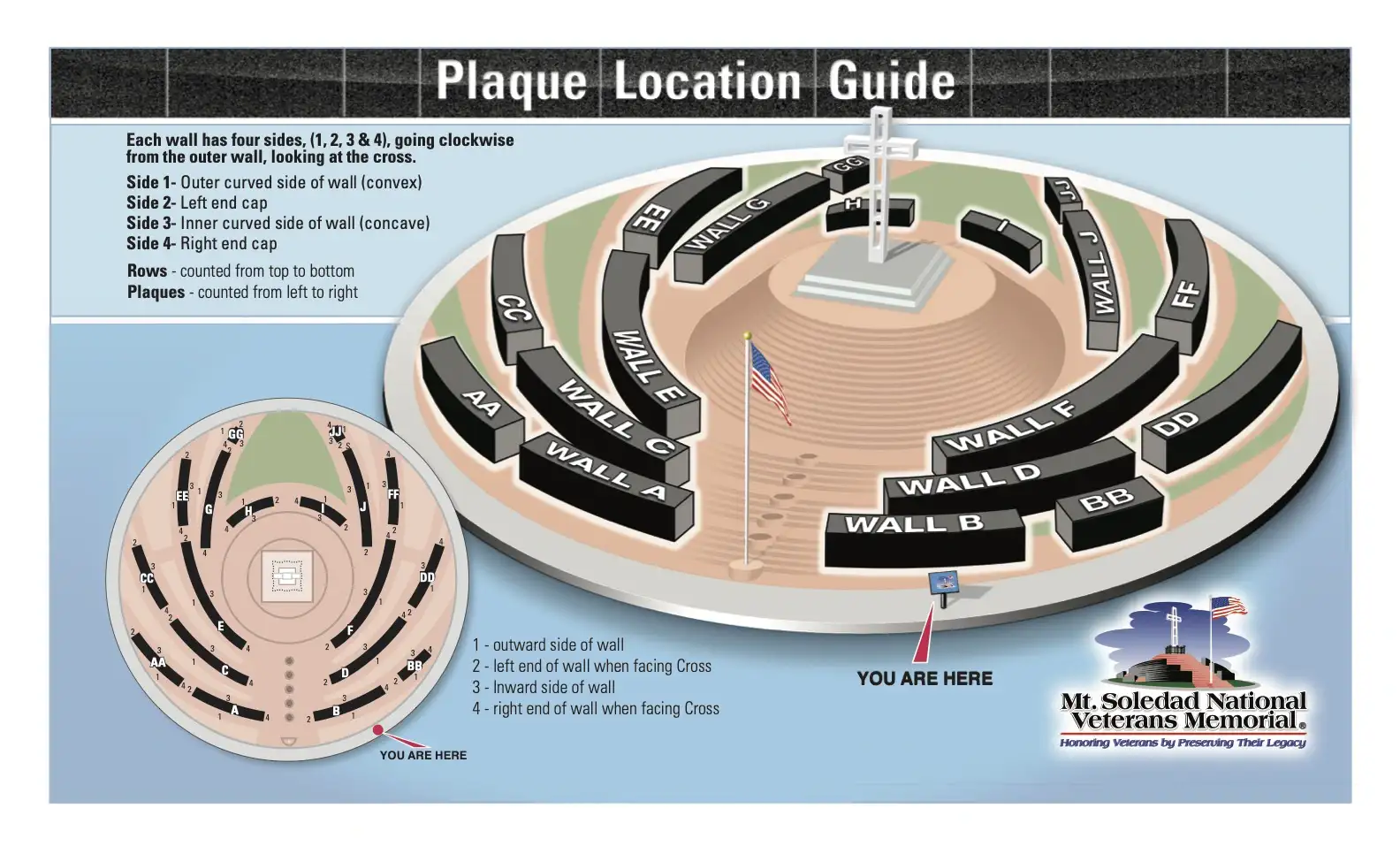

| Wall | CC |

| Wall Side | 3 |

| Row | 3 |

| Plaque Number | 2 |

As I saw the Invasion

By Sgt. George M.. Sports

4th Army Infantry Div.

1st Engineer Special Brigade

286th Signal Co.

“Naval Shore Fire Control” Sq.

We were the Naval Shore Fire Control party. We directed the fire of the destroyers, cruisers, and battleships on targets close in and behind the enemy lines. We operated on somewhat the same basis as the field artillery. Part of our men came ashore in the first wave --

that’s the Army spotters’ team. The other part, known as the Naval party, came ashore with the battalion commander, on whatever wave he desired—where he felt he was most needed.

Our Army party was composed of 1st Lt. Roger J. Allen, as spotter; Sgt. Barvinski, as chief of section or forward scout assisting the Army spotter; T/5 Peters as radio operator; Pvt. Collier, Pvt. Botko, Pvt. Tobb, as wire men. These men landed in the first wave, in support of “G” company, First Battalion, 8th Regiment, 4th Infantry Division. “C” Company was the assault company.

The Naval party came in on the fifth wave. It consisted of Lt.(j.g.) Palmer, Naval liaison officer; T/4 Winham, chief radio operator 284; T/5 Sports (that’s me), junior radio operator; Pvt. Wells, radio helper; Pvt. Matisklla, radio operator 609 (frequency modulated); T/5 Kreigel, junior operator 609.

The spotter team goes in with the assault company commander; the Naval liaison officer is with the battalion commander, whenever he’s needed. That’s how we operate. It sounds somewhat complicated but in action it gives coordination of sea, land, and air forces.

The Naval Shore Fire Control was used for the firs time during this invasion of Normandy.

D-Day to D+28th Day

Our Infantry Battalion Commander was Lt. Col Simmons. He received the announcement of D-Day on June 5th, about 3:30pm., on board the USS Dickman, our transport.

Everyone was quiet during the announcement, nut it didn’t seem to affect was the way I had expected. He gave us a short talk-”This was what we had been waiting for.”

We got up early on thee morning of June 6th,, about 3am. We had a good breakfast and all ate and talked as if nothing was going to happen. As we were preparing to load in the landing craft, we exchanged autographs and home addresses.

I was in the boat with the Battalion Commander, known as the free boat. I have never seen such rough water. The bow of the landing craft was straight up and then the stern. After floating around out there for half and hour, getting in the right wave, I was so sick I didn’t think I’d live. I’ve heard a lot of talk about being so seasick you cared not if you lived or died and what’s how I felt. So as we came near the line of departure, I was so all in I didn’t care whether an 88 hit our craft or not. They were coming at us from all directions. Just before we hit the line of departure, we saw something that looked like 4th of July fireworks. Our C-47’s were taking our paratroopers in and the Jerries were sending up ack ack of all colors It was beautiful—but we knew what was behind it. Hell—and plenty of it, It was a sight to remember.

As we traveled toward the beach, we saw landing craft that had been hit by mines and sinking fast. We passed sour destroyers in their firing areas, throwing down their bombardment; also cruisers and battleships. It was comforting to know that the Navy was supporting us. You’ll find out later what it meant so much to us.

When we hit the line of departure, our control boat left us to mark the line. We were then on our own, full speed ahead to shore. As we got close to the beach, we were given the signal to get low in our craft and brace ourselves to hit the beach. When we hit, the ramp was lowered—and every man for himself. We really had the odds against us. Every kind of weapon was firing at us from everywhere—88’s, screaming mimies, machine guns.

We landed H+1 Hour after the assault troops. It was a living hell. Men were lying everywhere—asking and crying for help—yet we had to press forward, leaving most of them to do the best they could. Men wounded and bleeding were digging a hole with one hand in the sand to make a cover from enemy fire. It was awful! At that time, we had very few side men, but the few we had surely did a swell job.

As we hit the beach, my battalion was in the center, the third was on the left, and the second on the right, We then started over the sea wall and the sand dunes beyond, with machine gun fire and 88’s coming at us from all directions. We got over—only to find our fellows had run into further difficulties. The whole beach from the far end of the third battalion to the far end of the second was mined. Our boys were lying there wounded, calling to us to watch our step—the whole field was mined. We didn’t know where to step next. That’s when I started thinking of everything I ever did wrong.

Well,, we knew we had to go forward—no turning back then. So, we trusted God and got down low and kept going. We got through okay, except that one of four men was missing. We then contacted our Army spotters for the first time. I was good to know they were all okay.

Our next blow was on a small French village. As we advanced along a small trail, we ran into a mortar battalion. The artillery observer called for support, and soon the target was knocked out. We had quite a few casualties. I spoke to a captain was had gotten an arm wound—and he said that if hell was any hotter then it was up there we was changing his way of living.

By this time, it was getting dusk on D-Day. I heard a great noise in the air, coming from the channel side. My hopes brightened—I was certain it came from our planes. Yes, our famous glidermen. You’ll never know how glad I felt. So many came and so fast I couldn’t count them. I looked up as long as possible—until my neck became so sore I couldn’t look up any longer. They brought relief to everyone’s heart. They seemed to be coming for hours—so near the tree tops we could almost see the glider pilots, and we could see the gliders being disconnected from the C-47’s.

We continued to advance until we got fairly close to the village. We slowed up about midnight, along a road near the village. By morning we were ready for the attack, We started to move out—only to find we were almost entirely surrounded. Rifle fire came from everywhere. They pinned us down with machine gun and rifle fire. We couldn’t raise our heads above the hedge—there were snipers in every tree. We were only a short distance from our paratroopers, and overnight the Germans had planned a counter attack to try to cut us off from our paratroopers. We could neither fight nor advance. “B” Company, on our right,, was contacted and ordered to attack from the flank. The Germans turned on them and we were then able to advance, We fought through hell for that village—yet it had looked so small. We got about 315 prisoners at one time. As we entered the village, we found it was a company headquarters. Our lieutenant got the flag there, There were a few snipers around but they were soon taken care of.

A French woman came out saying something. One of the boys, who could speak French, walked over to find out what it was. She said there were two Germans in her home. A couple of the boys went in after them, and came back with two men in civilian clothes. They said they were the French woman’s sons—we asked her if this was true, and she said no. One of the boys took them back to the rear.

We then advanced along a hot, stinking road, heavily mined. The trucks were directed to another route. We continued the advance for about five miles before we contacted the enemy.

We tried to flank their position and finally did—but it was tough. We were with Company “C” at that time. They were on the line at the time of the contact with the enemy. Company “B” was in reserve. Company “A” was supposed to hold its present position. As we started to the flank, some of my section were left behind with Company “B”. I was with Company “C”.

We had a large opening to cross, and most of us got through before the enemy observer picked us up. After crossing the open field, we advanced through a swamp which concealed us from the enemy, only a short distance away. After what seemed a long time, we got through the swamp. I was then given ordered to go back to the position we had just left and pick up the rest of the men. Without rest, I started on my long, wet, tough trip back. I was about halfway through the swamp when the enemy spotted some members of Company “B”, at the location to which I was returning. I was between the enemy and the target. The shells began to fall all around me in that awful swamp. But I kept going.

I finally reached the open field, which was under machine gun fire from the enemy. I started to make the opening with all my speed, when the Jerries opened fire, I hit the ground and had to crawl the rest of the way to where I would have concealment—about 100 yards.

I found the men I had come for and we started the trip back. We tried to make the open field but had to turn back. There were too many of us. The enemy opened up with their artillery, and for thirty minutes they really threw down a barrage. So we had to change our route—they knew our location and we had to get out—but quick. We went around to the right side of the swamp, and started advancing through artillery barrage. As we advance along the edge of the field, we could see cows dropping as the shells burst.

Some of our men did not make it—yet we were lucky, for we survived the artillery barrage with few casualties. After we had advanced a few hundred yards, we ran into some snipers. They delayed us somewhat, but they were soon cleared out and we continued to advance. By this time we were back on the right track and saw quite a few of Company “C” men who had fallen along the roadside.

We finally came to a crossroad where all the trouble had come from. We saw one of our tanks with its track knocked off. Down the road I saw a German truck that had been pulling an 88 (artillery and anti-aircraft combined). It had been knocked over in the ditch and was burning. The driver and gun crew had been killed. We advance about 500 yards and bedded down for the night, We slept okay, except for disturbance from a couple of snipers,

We got up rather early, had a bit of “C” rations, and were on our way. We advanced rather slowly. We had gone about two and a half miles down the road when we contacted a company of enemy infantry. We quickly got into position, and in about thirty minutes they opened up with their artillery. My Naval officer, Lt. Palmer, and I were sent up to the front to locate the enemy gun battery. We had no observation other than trees. I ordered the ship too stand by ready to fire, turned over the radio to the other operator, and went up to operate the telephone as Lt. Palmer was going up a tree for observation. He sent down the location of the target, and I was sending it to the operator on the other end, when I heard an M-1 rifle shot. I just happened to look up and saw Lt. Palmer sliding f=down the tree. I reached up and caught him as he hit the ground. He had been shot in the upper part of his thigh by one of our own doughboys, who thought him an enemy sniper. We gave him first aid and sent him back to the field hospital. The last time I saw him, he was leaving on a Jeep.

The gun battery had been knocked out. As we advanced, one of our tanks that had received a direct hit on its turret was burning. Up the road about 200 yards I saw an awful sight. One of the enemy gun positions of a horse drawn artillery battery had suffered a direct hit. Beside it lay the bodies of the men, their clothing still burning. One of the horses, in an attempt to get away, had reached a small wall close by and was burned there with his front feet over the wall, in such a position that he looked like a statue. There was an awful smell of burning flesh. Thus the enemy paid dearly for what we lost.

Five Points

We then moved up into an intersection known as the Five Points. The Naval Shore Fire Control was ordered to stay with the reserve company until needed. We were with the reserve company that late afternoon. But at dusk the company was pushed up to the front to relieve a company on the line, and we kept on going with the company. We had heavy radio equipment, and couldn’t travel fast. We reached a point about midnight where we were ordered to bed down.

I was very much surprised when a German machine gun awakened me at n early hour. I thought we were still in reserve—but I did not think this for long. I was in a ditch sleeping when this machine gun started clipping the tops off the grass above my head. By that time, my buddy informed me that our lieutenant had put us just across the road from the Jerries—and let’s get out. Without raising my head above the ditch, I crawled until I had a chance to run for it. I rejoined the others at the Five Points.

The company commander called for the Navy to knock out some machine gun positions that were holding up our advance. I set up my famous 284 radio and contacted the ship. The ship was ready to fire—waiting for the target location. B ut my officer had difficulty getting a position to observe from. There was only one thing left to do—go up a tree and observe. This time the doughboys were notified not to shoot at the observer, and up he went. But he went up the wrong side and the German observer spotted him. They had very little adjusting to do, as they had every crossroad “zeroed in.” They opened up with their artillery—I never saw as much artillery fall in one place as it did there. I was on the radio waiting to fire the ship, but it got too hot for the observer so he came down.

By that time, the barrage was plenty heavy. I kept telling the ship to stand by—and then a large piece of shrapnel hit the radio and spun it around. That was too close! I told the ship that was all, closed down the radio, and took cover. There was a half-tack in the center of the crossroad loaded with ammunition. Everyone expected it would be hit next—when someone jumped in it and drove it back to the rear.

The artillery observer called for an observation plane to go over the target as no ground observer could observe from the present position. The request was granted. The target was an artillery battery position and the air spotter soon destroyed it. Quite a few men were killed there. We had to use everything we had to take the wounded back to the field hospital. It took us two days and nights to get away from those famous Five Points.

Montebourg

Our next big objective was Montebourg. We pushed on slowly and contacted the enemy about a mile up the road. It was at a French courtyard that the Jerries were using as a command post. Our tanks attacked first to knock out the battery of light artillery just beyond and to the left of the command post. Our first tank went into position and got a direct hit in the turret. It went up in flames. Two more tanks were sent up—one took the extreme left flank while the other moved up under cover, The Jerries fired a couple of shots at the tank moving up. Meantime, the tank on the left located their position and opened fire. While these two were exchanging fire, the other tank moved into position so as to get a good view of the target. The two soon wiped it out, then the doughboys moved in and the mopping up started. Many prisoners were taken there. There were dead Jerries in the ditch and everywhere. I saw one make a dash for it, and a doughboy opened up with an M-1—he got him in the center of the head—a perfect shot.

We then moved on our way to our objective. As we started out, it seemed as if the whole German army had broken loose. Screaming mimies, 88’s, everything was thrown at us. It seemed to me the end was just around the corner. I really was afraid.

We, the Naval Shore Fire Control, opened up fire along with the USS Nevada (battleship). Also, the artillery opened up. We would cease firing and then the Jerries would show up. I was really getting mad. We again opened with the Nevada, and our heavy artillery.

I couldn’t see how anything could be left standing. We moved into the town that night. We had one company to hold it.

At dawn, the Germans launched a counterattack, and we had to withdraw under heavy artillery barrage. We withdrew about one thousand yards, secured our line, and got set for them. But they did not attack as we had expected. Everything seemed to be quiet on the front the early part of the night—only thing we could hear was a German machine pistol and a U.S. 30 caliber machine gun in the near distance. One would fire and then the other—just answering each other. We couldn’t possibly sleep—and I had had very little sleep until then. About midnight someone yelled, “Gas!” Everyone scrambled to get their masks on—only to find it was a false alarm.

The second attack took place early in the morning. We went in with big force, I have never seen as many dead bodies. There was a regiment on bikes that tried to get away. Our men had every road covered—as they started down the road toward Valonges, our doughb9oys were there. As they came by, they mowed them down with 30 caliber machine guns. Bikes and dead Jerries had the road blocked so you could hardly pass through. It was an awful sight.

At this time, I left the 1st battalion of the 8th regiment. I was sent over to the extreme coast side with the 22nds regiment, 3rd battalion. It was the same division. They were having quite a bit of opposition over there. We joined the 9th section of the Naval Shore Fire Control, and I took part in the battle of Queensville.

We pushed up the coast to take four pillboxes which were to be our observation posts, so as to fire the Navy guns on German fortifications farther up the coast. It was then that I saw things that seemed unbelievable. Our battalion command post was about one thousand yards short of the pillboxes. We went up with the line company—the 9th and 1st sections of Naval Shore Fire Control took turns going up. It ws my day to go forward. Lt. Allen, Winham, Chorey, Ensign Murphy and I got up there rather early in the morning—to find that the Jerries had planted mines around the pillboxes. We managed to get through and reach the pillboxes.

There was ammunition in two of the pillboxes, and we took the one nearest the enemy so as to have better observation. We established our observation post and got set to fire. Ensign Murphy took his map and got on top of the pillbox, to be certain he had the right target. We sent the location to the ship, US Texas, and she fired a two-gun salvo. It was adjusted and a four-gun salvo was requested. We got it. But by the time the German observer had spotted Ensign Murphy on the pillbox. They sent one round behind us, but we continued to fire. They then send one round short. We, as observers, knew what to expect next. They had our position—they had our range—and what do you think would happen next? They fired another round, but it was slightly over. By that time Ensign Murphy was down from the top of the pillbox =, and we all took cover. Again, I thought of everything I had ever done wrong.

Winham and I pulled our radio into a trench, and made haste for the pillbox. The shells were 88’s, and we knew that 88’s wouldn’t affect the main part of the pillbox much. By that time, they were firing for effect on us. Winham and I just made it to the door and stepped inside. Winham was just closing the big iron door when an 88 landed at the bottom of it. He didn’t have time to latch it. A split second later and Winham, myself, and about fifteen doughboys would have been killed instantly. By then, I was plenty nervous. I have Winham to thank. There were some who did not make it.

The pillbox had ammunition in it—and as we crouched low and the barrage increased, we feared that a shell close by would ignite the ammunition; they still had their fuses attached.

All of a sudden I heard a pitiful groan from outside, asking and crying for help. Although the aid men were there, they couldn’t help. Yes, he was dying. It was an experience I can never forget. It was my first experience of the kind, and I hope it will be my last.

Finally, the firing was over and we came out—to find the entrance to the pillbox blown up. We were fortunate; we had few casualties. Two were killed and several wounded. What happened to the wounded after they left there I never knew. We had been saved—but deep down in our hearts was our feeling for the boys who were not there.

We began to try to locate the German gun battery. We found a pair of German field glasses which Lt. Allen took and set up beside a hedgerow. We picked up pillboxes farther up the coast, but could see no one around them. Then we spotted a small clump of trees, something that looked like an enemy bivouac area. We sent their position to the ship, US Nevada, and she opened fire with a two-gun salvo. We had fired only about four salvos when Lt. Allen called over to where I was and said, “Take a look.” I looked through the field glasses and saw Jerries loading in trucks, walking, getting out in whatever way they could.

In the meantime, we had contacted our air support, By that time, fighters were over their target. Well, you know what the air force did, They strafed the column, and at the same time Lt. Allen was having the US Nevada firing straight down the road. We had their right deflection, so Lt. Allen just increased the range each time he fired and followed the column straight up the road. With the fighters and the Nevada, we really fixed that column up right. When it was over, I looked again through the field glasses. I saw a road full of dead Jerries and smashed trucks. I didn’t see anyone walking around everywhere. So, they paid dearly for the two lives we lost.

We were still reducing the many enemy forces, besides the high ground we got. We then started for the battalion command post—Lt. Allen, Winham, and myself.. We came to a small house near the road leading out of Queensville, and found a barrel of cider waiting for us. We really took advantage of it. We were soon on our way to the command post when out of the blue sky a mortar shell landed between us and thee command post. We heard it coming from behind the command post—we knew it must be our mortar, and so it was. They were firing short. A second shell landed—and too close for comfort. No one had to tell us to hit the ground—we fell right in the middle of the highway. After that—lucky for us—no more shots were fired.

We finally got to the command post—hungry, tired, and in need of water. To our great surprise, we found our man who was missing on the beach. It really was good to see him and know that he was okay. We all had a chat, and started to prepare for a nice meal-yes-”C” rations again! Then we dug in and prepared to get a little sleep. We really needed some about then.

We next moved forward through Montebourg to take a high hill before Cherbourg, It was the following night that I saw Montebourg in flames. I couldn’t see a building standing, except the ones that were burning. I rode through Montebourg on a truck loaded with gasoline.

We came to a street with burning buildings on both sides, sparks flying everywhere. The driver gave us the word to hold tight. We all ducked low to pass through, and we made it okay.

We then took up positions outside Montebourg for the night. The following morning we were told to move up about two miles to a forward command post. To travel light, we took very little water and no rations. But instead of two miles, we hiked almost all day—at least fifteen miles. We got fairly close to the hill we wanted, and ran into a couple of platoons of Jerries, deep in the reverse slope of the hill. We took care of them, but by that time the enemy opened up with 88’s, followed by their “long Toms,” They were firing over us at our artillery position. Then our artillery opened up with air burst. They were firing short, and the shells were bursting fifty feet high over the hill we were now occupying. We had to take cover immediately. The artillery observer ordered the guns to cease firing, but the 88’s kept on coming. We were ordered to leave that point and return to a certain place where the remainder of the Naval Shore Fire Control teams were. Wee stayed there that night, and the next day our Lt. Sent a Jeep back for mail.

In the meantime, there was a company of infantry nearby. We heard a shot and someone yelled. There was no enemy in that section, and we went over to see what was wrong. We found that the company was a reserve company coming up to the front. They had never been in combat before, and one kid got nervous and shot himself in the foot. The way he yelled we thought he was being murdered. The doctor sent him back to a field hospital.

By this time the mail was in. It was our first mail call since we landed. I got twenty-eight letters. It was then, on June 17th, that Winham first knew that his kid had been born on May 18th. He was a happy man, and I can’t say I blame him! I also received an announcement from his wife.

I was halfway through my mail when two enemy planes came over. It was only a short time until our fighters were right behind them. They had our markings and at first we thought they were ours. We soon found out differently—for then the dog fight began upstairs. The shots from the planes were so close we had to take cover. Soon the ME-109’s had had enough, and tried to make a run for it. In so doing, they came over our position again and dropped a couple of bombs—just a hedgerow beyond me. Our planes were right on their tails, and brought both of them down a couple hundred yards behind our lines. I then finished reading my mail.

Our next objective was Cherbourg. We fought our way to some surrounding hills overlooking the town. We took the hills and had good observation of the town. The artillery

brought down fire on the town. We fired the Navy on it, and in the meantime, the Navy moved up the channel and fired at point blank targets in the port. There was a dugout in a nearby hill where the enemy was holding out. The air force bombed it and we shelled it. When it came time for the jump-off, our doughboys went in to mop up. They found it was like an underground hotel—food, beds, French whiskey, etc.

The port was heavily fortified, pillboxes everywhere. The Jerries built their pillboxes and later tore them down as prisoners of war. That was all I saw in the battle for Cherbourg up to then. I left on July 3rd for England, and landed in South Hampton on July 4th. And then a short rest. When we docked, we found the paratroopers of the Naval Shore Fire Control in port. We left together again, this time for a rest camp.

I am writing this just one year after it happened, without help of a diary. Some people say I have a good memory, but perhaps such experiences cannot be forgotten.

-- George M. Sports

Route 1

Blenheim,, S.C.

Footnote: The Naval Shore Fire Control was part of the 1st Engineer Special Brigade that landed at Utah Beach. After the war, the unit was awarded the French Croix De Guerre With Bronze Palm for valor during battle.

This account shall not be copied or used without the permission of a dependent of Sgt George M. Sports.

Plaque Wall Map