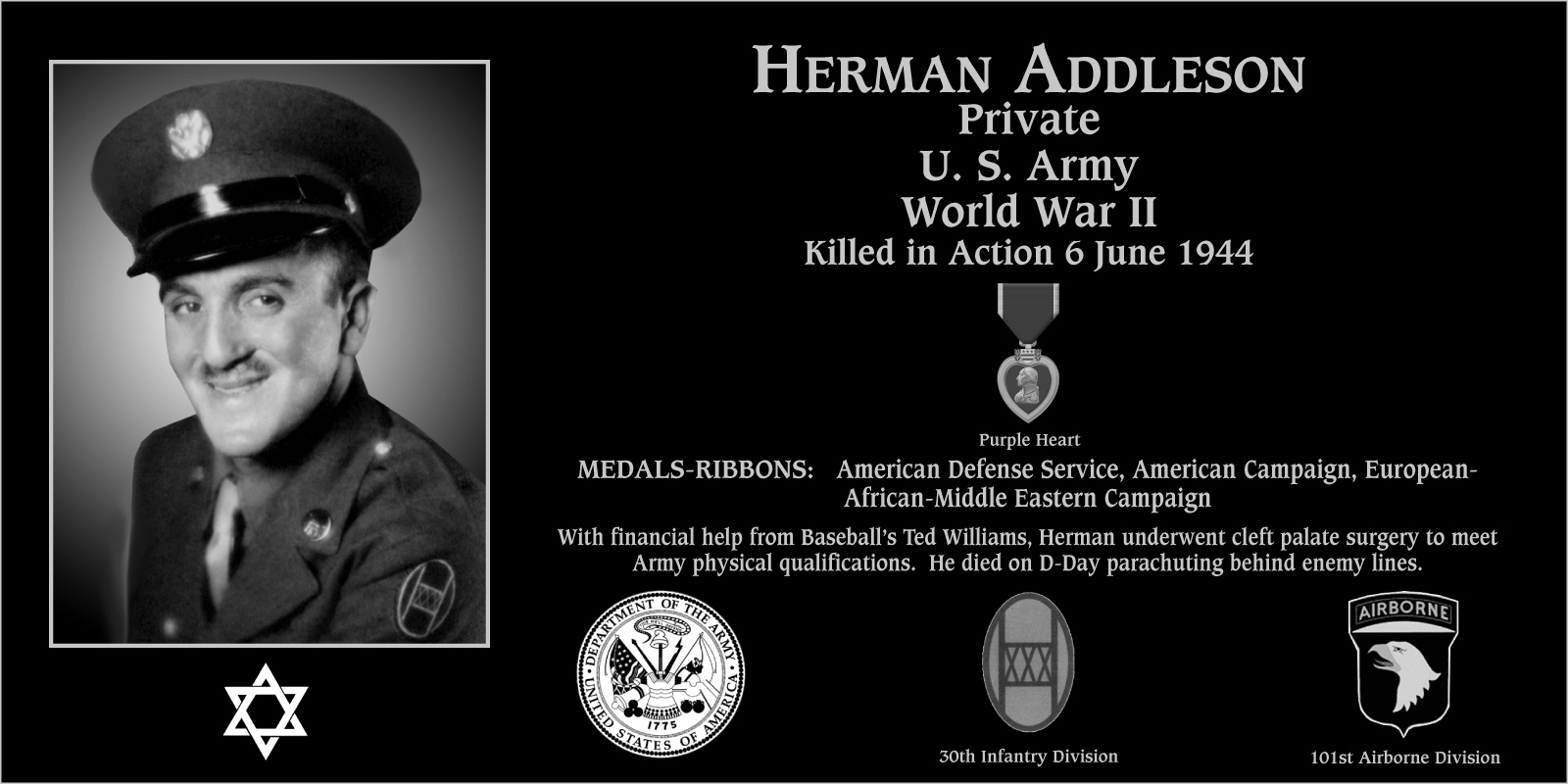

Herman Addleson

| Era | WWII |

|---|---|

| Branch | U.S. Army |

| Rank | Private |

| Military Decorations | Purple Heart |

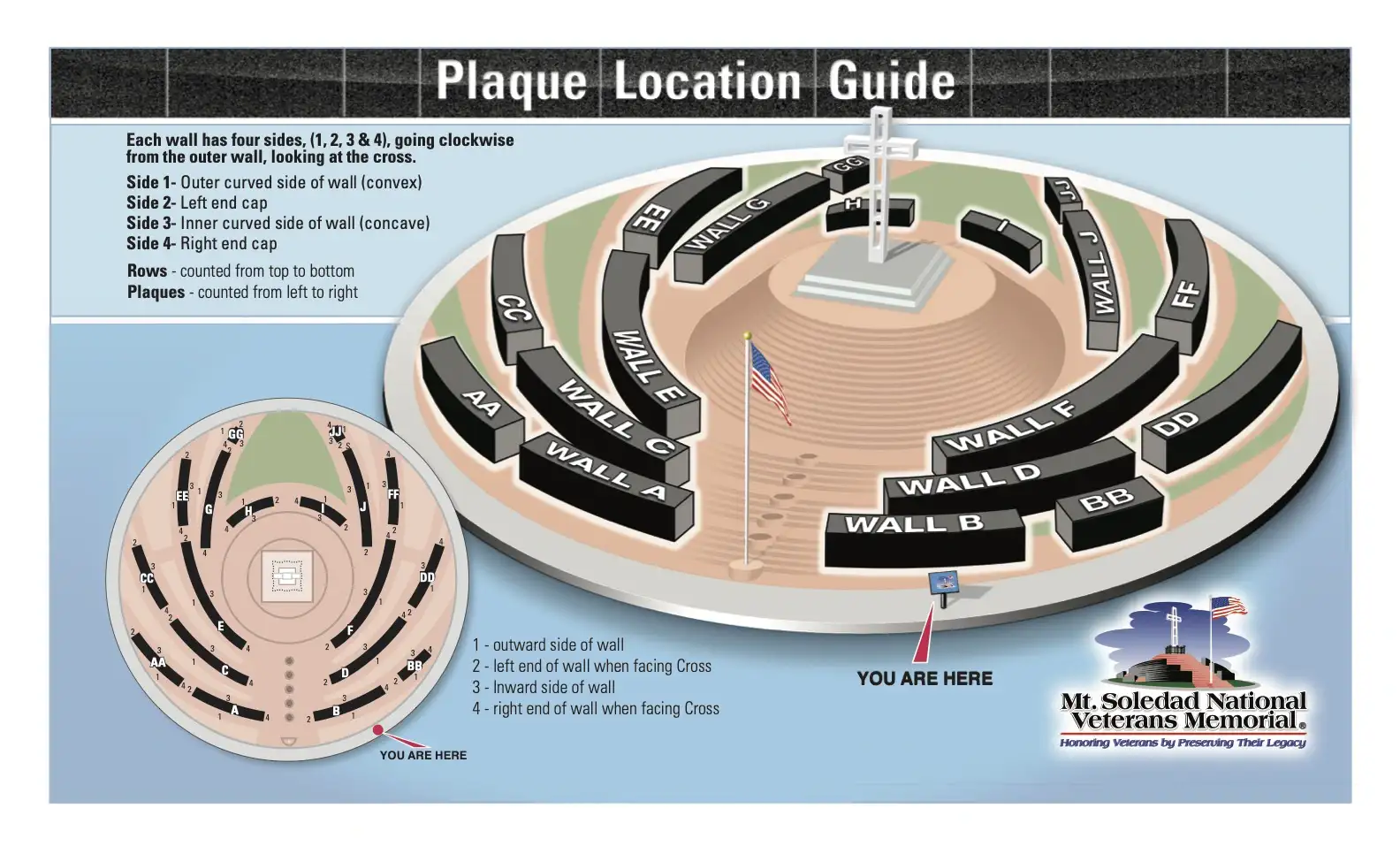

| Wall | BB |

| Wall Side | 1 |

| Row | 5 |

| Plaque Number | 9 |

MEDALS-RIBBONS: Purple Heart, American Defense Service, American Campaign, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign

With financial help from Baseball's Ted Williams, Herman underwent cleft palate surgery to meet Army physical qualifications. He died on D-Day parachuting behind enemy lines.

30th Infantry Division

101st Airborne Division

Plaque Wall Map